A friend gave me a copy of “The Alchemist” by Paulo Coelho and it’s one of the few books that I’ve liked well enough to keep in my personal library (I move a lot, so I try to keep the weight to a minimum). I’m not usually into “personal motivation” style books, however this book is the odd exception that I greatly enjoyed it (and have re-read it a couple of times and loaned it to friends).

The book centers on the shepherd Santiago, who has happily tended his flock of sheep and felt quite content for the lifestyle he has chosen. One night he dreams of a treasure buried at the base of the pyramids. Unsure what to do with this information, he eventually embarks on a quest to find this treasure (his personal legend) and encounters a host of people who help him, hinder him and provide insight on his journey.

As an allegory, the book explores the author’s views on the meaning and purpose of life, and how we get sidetracked from doing what we truly desire (and value). At one point he meets a Muslim man who has dreamed of traveling to Mecca his entire life, but has always found excuses why not to go. Eventually, after his interactions with Santiago, the Muslim man realizes that he has not gone to Mecca because he fears realizing his life’s dream, and losing his reason to live:

“Because it’s the thought of Mecca that keeps me alive. That’s what helps me face these days that are all the same, these mute crystals on the shelves, and lunch and dinner at that same horrible cafe. I’m afraid that if my dream is realized, I’ll have no reason to go on living.

“You dream about your sheep and the Pyramids, but you’re different from me, because you want to realize your dreams. I just want to dream about Mecca. I’ve already imagined a thousand times crossing the desert, arriving at the Plaza of the Sacred Stone, the seven times I walk around it before allowing myself to touch it. I’ve already imagined the people who would be at my side, and those in front of me, and the conversations and prayers we would share. But I’m afraid that it would all be a disappointment, so I prefer just to dream about it.”

Other characters have similar obstacles that prevent them from pursuing what they desire in life. Conversely, some characters are in pursuit of their personal legends, and their interactions with Santiago help them both on their journeys (he meets an Englishman trying to learn how to turn lead to gold, and falls in love with a woman whose personal legend was to find and love him).

Other concepts include paying to pursue our legends (he promises a gypsy 1/10th of his treasure to interpret his dream, and gives a king 1/10th of his flock of sheep for information about how to find his treasure. Between them they teach that everything in life has its price.

Allegorical Structure

This book probably wouldn’t have worked if it was presented as a literal guide to getting what you want in life. I’m not sure if this is a good thing or a bad thing. Perhaps the structure gives the impression of meaning to ideas that are tired clichés? Perhaps it is the best vehicle to convey ideas about universal human experiences – as soon as you become concrete, you lose the ability to convey your ideas to some readers? I have trouble pulling out specific strategies that I got from the book, and I’ve been hard in past reviews on other books that are short on specifics. This book did a good job of getting me reflect about what I want to do in life and what’s holding me back from doing it (conveying knowledge and a fear of failure respectively for the record).

How To Get It

The author doesn’t mind having his books pirated, however he doesn’t own the copyright for foreign translations (the original is in Portuguese) so you can decide for yourself if you’re comfortable finding and downloading a copy. It’s a very fast and easy read, and while some of the ideas are quite meaty, it’s digestible at multiple levels.

In your heart of hearts, what do you think you should be doing with your life? Or, if you don’t mind the theological overtones, what do you think is the purpose of your life? If you’re not actively pursueing this, what’s holding you back?

To order this book:

If you are from Canada then please use this link for Amazon.ca

From the United States then please use this link for Amazon.com

I’ve been amazed at people’s reaction to H1N1 for a number of reasons. I was *SHOCKED* that they were able to get the name changed from “Swine Flu” to H1N1 (people involved with the pork industry started oinking immediately after the pandemic started and amazingly managed to get it renamed). I still like to call it “the pig flu”.

I’ve been amazed at people’s reaction to H1N1 for a number of reasons. I was *SHOCKED* that they were able to get the name changed from “Swine Flu” to H1N1 (people involved with the pork industry started oinking immediately after the pandemic started and amazingly managed to get it renamed). I still like to call it “the pig flu”.

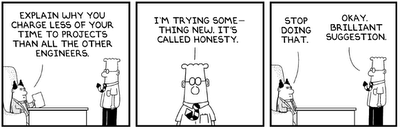

When you’re working with hard-core hackers, chances are they’ll understand what they’re working on FAR better than you do. Many people used to a traditional management role will be bothered by this. It means that you’ll have to ask questions and gather information from the techies working for you, instead of dictating things to them. Say they estimate it’ll take two weeks and you demand it be done in one? You’re going to have problems (if they *DO* deliver it in a week, I guarantee either it won’t work properly or your team will have killed themselves to meet the deadline, they can only do that so often). Say they recommend designing things one way and you demand they do it another? Chances are there are going to be unforseen (by you) problems with the design that could have been avoided by talking to the people implementing it.

When you’re working with hard-core hackers, chances are they’ll understand what they’re working on FAR better than you do. Many people used to a traditional management role will be bothered by this. It means that you’ll have to ask questions and gather information from the techies working for you, instead of dictating things to them. Say they estimate it’ll take two weeks and you demand it be done in one? You’re going to have problems (if they *DO* deliver it in a week, I guarantee either it won’t work properly or your team will have killed themselves to meet the deadline, they can only do that so often). Say they recommend designing things one way and you demand they do it another? Chances are there are going to be unforseen (by you) problems with the design that could have been avoided by talking to the people implementing it.