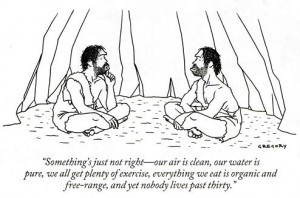

Mike and Trent are in Las Vegas and Mike has just lost a hand of blackjack after Trent advised him to double down.

TRENT: I’m telling you, baby, you always double down on an eleven.

MIKE: Yeah? Well obviously not always!

TRENT: Always, baby.

MIKE: I’m just saying, not in this particular case.

TRENT: Always.

MIKE: But I lost! How can you say always?!?

I’ve always been interested in how people learn and decide what is “truth”. Often people use the wrong approach to determining what is correct and incorrect.

With social or science issues, often people are swayed by anecdotal evidence. If we’re looking to shape public policy or understand how people function as a group, we need to consider them at the group level. It’s problematic for people, as we automatically relate to stories about individuals far more than statistics (that’s why McCain and Obama debated about “Joe the Plumber” and not about small businesses or the middle class). However, as enticing as stories are, it’s incredibly misleading to allow ourselves to be swayed by this.

With philosophy or religion, we are often swayed by a charismatic person shaping our early views. This is why children disproportionately share the religion of their parents: our parents have a VERY large impact on us during our early years (and often for the rest of our lives).

With investments, they’re often judged by their results, which is also the wrong way to think about them. In the lead in quote the characters Mike and Trent (from the movie “Swingers”) are arguing about this. Trent is talking about the optimal strategy to play blackjack (based on probability), while Mike is talking about what actually just happened in the hand they played (the results).

“Decisions can only be evaluated based on what the decisionmaker knew at the time, not on results.” – John T. Reed

In “Landlording on Auto-pilot” the author suggests an investment strategy where you buy one property per month until you’ve bought 100 properties. You allow these to appreciate for 4 years, then sell off 80 of the properties, pay off the mortgages on the remaining 20, then live off their income for the rest of your life. It’s a great strategy, provided you can:

- guarantee strong real-estate appreciation during the 12 years it would take to execute

- have each property cover ALL its monthly expenses completely

- not have any surprise emergency expenses (such as a roof leak or a water heart burst)

Any of these three is pretty close to impossible to pull off consistently (and would make you filthy rich if you could do so), so to manage all 3 for 100 properties would be pretty damn impressive.

I don’t think the author is being intentionally misleading when he recommends this. He’s probably had reasonably good luck during his accumulation phase and based on his results he recommends a VERY aggressive strategy (which is far more likely to ruin someone following it than lead them to riches). Casey Serin was doing something along these lines and managed to get himself over 2 million dollars in debt and headed for bankruptcy.

I like Derek Foster, his books and his investing strategy. HOWEVER, the justification he provides for his strategy is very much based on results. He bought certain companies over a certain period of time and managed to retire at a very young age. Would the same strategy work today? Would it have worked then with a different set of stocks? Will it work indefinitely into the future? These aren’t easy questions, and a number of commentators have questioned this. Again, I believe Derek Foster is sincere in his confidence in his investing strategy and is honestly trying to help fellow Canadians become better investors. I think there’s a fair bit of good stuff in his books, and they helped me get the (limited) understanding I have of equities. I also think bloggers and journalists have asked him some good questions (that haven’t all been answered). The biggest danger would be if he got lucky picking the right strategy for the market we were in and his results may not be easy to repeat.

Some may ask “well, if their strategies don’t work why did these two guys make a lot of money doing it?” The simplest answer is that the people whose strategies didn’t work aren’t writing books about it (surviorship bias – we’re only hearing about lucky ones).

The ultimate example of this may be the lottery winner who advocates winning the lottery as a retirement plan, since he made $30 million! It’s true that it worked out for him, but what if it hadn’t? Is it a good idea for the rest of us to try and follow in his footsteps?

One of my bonehead uncles (as always, I’ll point out that we’re only related by marriage) once made the assertion that after world war 2, Britain invested in rebuilding houses and in consumer goods, while post-war Germany was forced to invest in its industry (while the population continued to suffer from war damages). He claims that the strong modern economy in Germany, compared to Britain, proves that this was the superior policy. While I’d be willing to discuss the policy and it’s impact, it is an utterly IDIOTIC assertion to make that the relative strengths of their modern economies “prove” this point. The two countries have radically different populations and geography, and have gone through over 60 years of a HUGE variety of differing policies. If all we use to evaluate these policies is the current state of their economies, that would imply that EVERY SINGLE economic decision Germany has made since the war was correct (and EVERY SINGLE economic decision Britain has made was incorrect), since “Germany has the stronger modern economy”. This is foolish. Their economies were impacted (positively and negatively) by ALL these decisions (and a large number of other factors thrown in).

Similarly, with anything we want to judge “by its results”, we must consider not just the philosophy or general approach but the specific execution of the strategy, and the environment it worked in.

The “

The “